exhibition

SAVED BY BEAUTY

- Foreword

- Notes de passage

- Intermezzo

- Dostoevsky, beauty, and America

- Epilogue

- Postface

- About the Artists

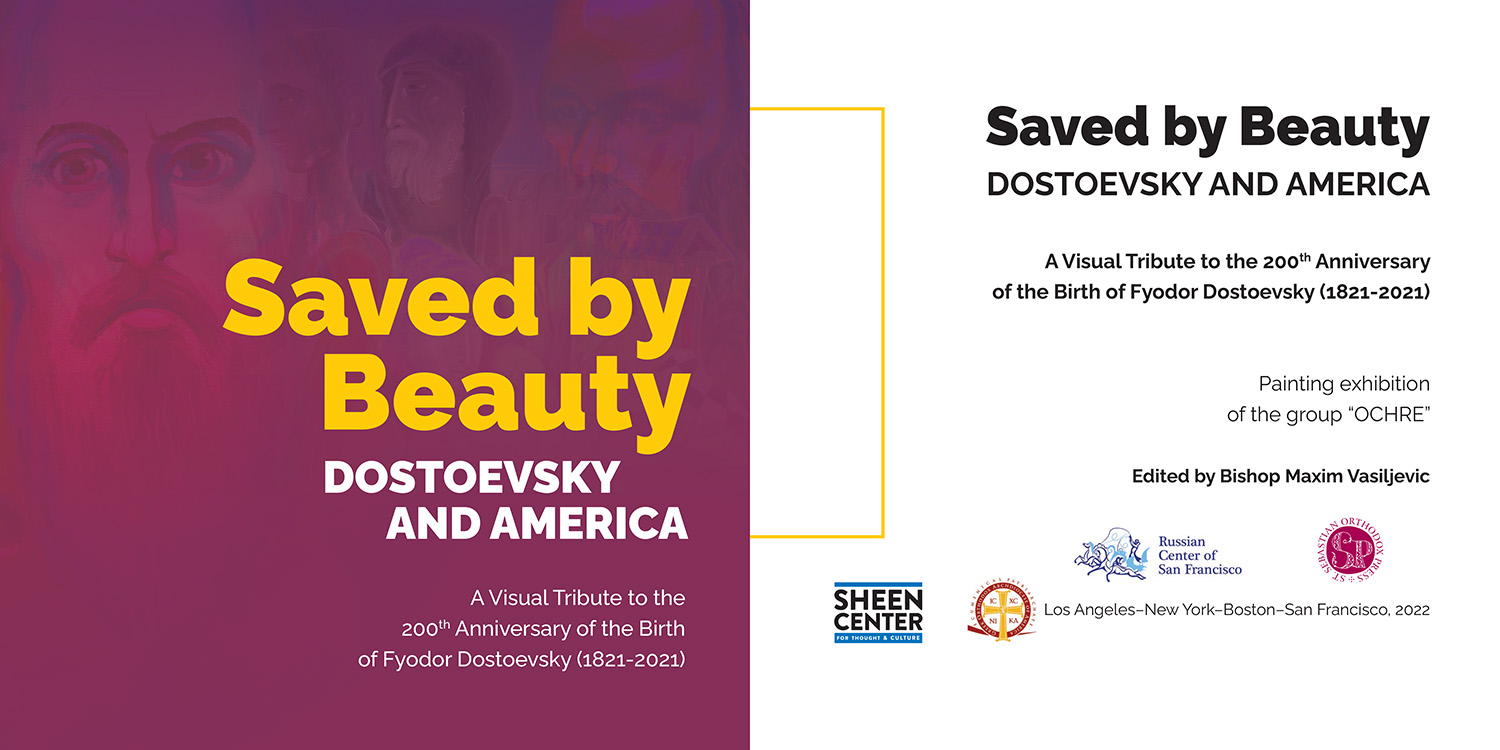

A Visual Tribute to the 200th Anniversary of the Birth of Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-2021)

The bicentenary celebration of the birth of the great Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-2021), considered one of the most outstanding writers of modern literature, has found the world in an increasing state of bewilderment. Some believe that the dynamic and open anthropology of this classic can help rectify an issue because it has the power to break the defensive armor of the modern ego and take us beyond its ideological constraints.

Having toured Greece and New York at The Sheen Center, the “Saved by Beauty” international art installation premiered in Boston at Maliotis Cultural Center through July and at the Russian Center in San Francisco through August-September. I am especially grateful to these three centers for hosting this important show. This exhibit is a tribute to literary legend Fyodor Dostoevsky in the two hundred years since his death. The pieces reflect aspects of the author’s life and struggles as well as characters and scenes from his famous novels and seek to awaken in us a sense of a deeper spiritual reality and a transformative beauty that, as Pope Benedict writing about Dostoevsky said, “unlocks the yearning of the human heart, the profound desire to know, to love, to go towards the Other, to reach for the Beyond.”

I also want to acknowledge the essential roles of Professor Peter Bouteneff from St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, Professor Michael Ossorguin from Fordham University, and Professor Timothy Patitsas from Hellenic College in Boston, who have contributed mightily to the dissemination of this Exhibition.

The paintings on the walls of galleries in Athens, New York, Boston, and San Francisco, show Dostoevsky, a man, dressed in flesh and blood, who lives, suffers, falls, and rises. At the same time, these paintings are a result of a “non-Euclidean” reading of that reality. Fyodor creates art or beauty by confessing what is in his soul, hence its astonishing persuasiveness.

We never seem to think of Dostoevsky’s characters absolutely in terms of themselves but rather in terms of the ideas they personify. Bakhtin said that some underestimate the deep personalism of Dostoyevsky, which is wrong. Because for Dostoevsky, there are no “ideas per se” or “ideas of anyone.” Although the ideas they display are essential, to appreciate Dostoevsky’s achievement, we must look at his characters as beings of interest in themselves and not just through them to what we think the author is using them to say. Dostoevsky presents even the “truth in itself” as embodied in Christ, as a person who enters into relationships with other persons.

The depth and contradictoriness of his heroes have made systematic psychological theories look shallow by comparison. Aware of the relativity of categories of morality in human life, this Russian writer was the first to show that the physical and psychological boundaries within the context of human diversity are neither so clear nor unyielding.

The painters of the visual group “OCHRE” have attempted to visually express Dostoevsky’s world of hopeless, dark heroes and others, positive heroes, who have experienced repentance. According to Fr Stamatis Skliris, “this exhibition shows many visual trends. Some works are more emotional and more romantic, or even darker. Some seek to describe scenes from Dostoyevsky’s novels; some are portraits of his heroes, others, more existential, penetrate the Dedicated streets of the psychic world, while some move into a spiritual bullet showing spiritual points and messages broadcasting the work of the great writer. The entire exhibition awakens our spiritual restoration and serves as a reminder of the first literary adventures of the psychological novel. It expresses nostalgia for the great literary genre called novel, which was popular in the author’s years, and nowadays it fades away.”

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky’s work, according to Fr. Stamatis, is like a submarine diving into the bottomless depths of the human soul and photographing its Dedalian landscapes to present them before our eyes as a realistic image of enigmatic existence, which, as long as there is, fights nonexistence.

Dostoevsky’s sense of evil and his love of freedom made him especially relevant in a century of world wars, mass murders, and totalitarian systems. His portrait suggests a person who lived the experience of seeing an abyss before him, and he looks at nothingness directly with his eyes. The great writer is characterized by eternal restlessness of spirit, and he insists (constrained by this effort) on a twofold feeling that we would call, “waiting for the arrival of nothingness.” It is as if he is above the abyss and watching his pens and notebooks flee, his table sliding, and his body, his house, above the abyss. He lived this feeling so intensely that it permeates his existence with the atmosphere of various scenes that he creates with his imagination in his work.

The gaze of the long-suffering, but blessed Dostoevsky crystallizes in that portrait. When we look at him and his eyes and then his torn coat, we can say: this man has gone through a storm, yet his eyes possess a sweetness that says: Thank God, we are saved! According to Metropolitan John Zizioulas, “Dostoevsky brings us to the edge of the abyss but does not leave us to fall into the abyss.” And Dostoevsky’s message to everyone is: “Compassion is the most important and, perhaps, the only law of existence for the whole of all mankind.” In his prodigious literary works, this Russian novelist and short-story writer refer to repentance and redemption as preconditions of becoming God-like.

As Vasileios Gondikakis (the archimandrite of Iveron Monastery on Mount Athos who learned Russian only to read Fyodor in the original) said, “if you seek what is honorable, what is good, you cannot read Dostoevsky and remain the same. You cannot read him, accept his message and then simply forget it. He becomes yours, and you his. You are entwined with each other in a deep, exalted, wide space, in the open space that belongs to everyone and where everyone fits in.”

Bishop Maxim of Western America

Having toured Greece and New York at The Sheen Center, the “Saved by Beauty” international art installation premiered in Boston at Maliotis Cultural Center through July and at the Russian Center in San Francisco through August-September. I am especially grateful to these three centers for hosting this important show. This exhibit is a tribute to literary legend Fyodor Dostoevsky in the two hundred years since his death. The pieces reflect aspects of the author’s life and struggles as well as characters and scenes from his famous novels and seek to awaken in us a sense of a deeper spiritual reality and a transformative beauty that, as Pope Benedict writing about Dostoevsky said, “unlocks the yearning of the human heart, the profound desire to know, to love, to go towards the Other, to reach for the Beyond.”

I also want to acknowledge the essential roles of Professor Peter Bouteneff from St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Theological Seminary, Professor Michael Ossorguin from Fordham University, and Professor Timothy Patitsas from Hellenic College in Boston, who have contributed mightily to the dissemination of this Exhibition.

The paintings on the walls of galleries in Athens, New York, Boston, and San Francisco, show Dostoevsky, a man, dressed in flesh and blood, who lives, suffers, falls, and rises. At the same time, these paintings are a result of a “non-Euclidean” reading of that reality. Fyodor creates art or beauty by confessing what is in his soul, hence its astonishing persuasiveness.

We never seem to think of Dostoevsky’s characters absolutely in terms of themselves but rather in terms of the ideas they personify. Bakhtin said that some underestimate the deep personalism of Dostoyevsky, which is wrong. Because for Dostoevsky, there are no “ideas per se” or “ideas of anyone.” Although the ideas they display are essential, to appreciate Dostoevsky’s achievement, we must look at his characters as beings of interest in themselves and not just through them to what we think the author is using them to say. Dostoevsky presents even the “truth in itself” as embodied in Christ, as a person who enters into relationships with other persons.

The depth and contradictoriness of his heroes have made systematic psychological theories look shallow by comparison. Aware of the relativity of categories of morality in human life, this Russian writer was the first to show that the physical and psychological boundaries within the context of human diversity are neither so clear nor unyielding.

The painters of the visual group “OCHRE” have attempted to visually express Dostoevsky’s world of hopeless, dark heroes and others, positive heroes, who have experienced repentance. According to Fr Stamatis Skliris, “this exhibition shows many visual trends. Some works are more emotional and more romantic, or even darker. Some seek to describe scenes from Dostoyevsky’s novels; some are portraits of his heroes, others, more existential, penetrate the Dedicated streets of the psychic world, while some move into a spiritual bullet showing spiritual points and messages broadcasting the work of the great writer. The entire exhibition awakens our spiritual restoration and serves as a reminder of the first literary adventures of the psychological novel. It expresses nostalgia for the great literary genre called novel, which was popular in the author’s years, and nowadays it fades away.”

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky’s work, according to Fr. Stamatis, is like a submarine diving into the bottomless depths of the human soul and photographing its Dedalian landscapes to present them before our eyes as a realistic image of enigmatic existence, which, as long as there is, fights nonexistence.

Dostoevsky’s sense of evil and his love of freedom made him especially relevant in a century of world wars, mass murders, and totalitarian systems. His portrait suggests a person who lived the experience of seeing an abyss before him, and he looks at nothingness directly with his eyes. The great writer is characterized by eternal restlessness of spirit, and he insists (constrained by this effort) on a twofold feeling that we would call, “waiting for the arrival of nothingness.” It is as if he is above the abyss and watching his pens and notebooks flee, his table sliding, and his body, his house, above the abyss. He lived this feeling so intensely that it permeates his existence with the atmosphere of various scenes that he creates with his imagination in his work.

The gaze of the long-suffering, but blessed Dostoevsky crystallizes in that portrait. When we look at him and his eyes and then his torn coat, we can say: this man has gone through a storm, yet his eyes possess a sweetness that says: Thank God, we are saved! According to Metropolitan John Zizioulas, “Dostoevsky brings us to the edge of the abyss but does not leave us to fall into the abyss.” And Dostoevsky’s message to everyone is: “Compassion is the most important and, perhaps, the only law of existence for the whole of all mankind.” In his prodigious literary works, this Russian novelist and short-story writer refer to repentance and redemption as preconditions of becoming God-like.

As Vasileios Gondikakis (the archimandrite of Iveron Monastery on Mount Athos who learned Russian only to read Fyodor in the original) said, “if you seek what is honorable, what is good, you cannot read Dostoevsky and remain the same. You cannot read him, accept his message and then simply forget it. He becomes yours, and you his. You are entwined with each other in a deep, exalted, wide space, in the open space that belongs to everyone and where everyone fits in.”

Bishop Maxim of Western America

André Gide wrote that “though pregnant with thought, Dostoevsky’s novels are never abstract, indeed, of all the books I know, they are the most palpitating with life.”

Having been gifted with the ability to dive deep into the realm of the subconscious, Dostoevsky soon realized how unpredictable human beings can be. His underground man insults his readers, then apologizes and berates himself, which culminates in his becoming aggressive, only to calm down a moment later. And the circle is repeated. He constantly pulls the rug under his own feet, and at the same time he is aware that he is trapped in the labyrinth of his character. He confesses and announces: “Hell, that’s me.”

Long before Sartre, and more disturbingly than Dante, Dostoevsky described hell in a similar manner, but more accurately: “I maintain that hell is the suffering of being unable to love.” Unlike Sartre, this definition of hell does not seek the cause of torture in others but only in oneself, “in my inability to relate to the ‘other,’ the tragic loneliness of my existential self-containedness, of my ‘freedom’,” as Yannaras lucidly observed.

By saying that “to love a person means to see him as God intended him to be,” Dostoevsky seems to have set eschatological expectations as the measure of existence in history. By not embellishing the conflicting image of the inhospitable world before him, Dostoevsky composes a grand symphony of life in which paraphony, cacophony and harmony alternate, and moreover coexist, giving us a complex but compelling anthropology.

When Dostoevsky rearranges the coordinates of reality in his storytelling (in one story, the snow falls horizontally), he helps the reader to flee from the comfort of the casual narrative. A grave monotony reigns over many devilish forgers of better and brighter futures (Verkhovensky, Stavrogin), whereas those who cherish life, even in bad times and with notable fluctuations in their fortunes, give off a resonance of hope. After all, the latter resonate with a universal frequency, which is why only such people experience a resolving crescendo that comes after a change of heart (metanoia) and repentance.

Although a profound psychologist, Dostoevsky does not assess the spiritual rebirth of man in Christ by human criteria alone, nor does he provide a documentary account of such a process. What he does is help us to see how much we have fallen into the trap of self-deception so that we do not dare begin the fight against inherent sinfulness. Whenever we achieve some moral victory, vainglory so muddles our minds that we begin to think that the pride engendered reflects our true self. Alyosha, though, tells his crafty brother: “The ladder’s the same. I’m at the bottom step, and you’re above, somewhere about the thirteenth. That’s how I see it. But it’s all the same. Absolutely the same in kind.”

Dostoevsky’s novels illustrate all poles of the antinomy of life, and they can stir us up in this age of transhuman technology. We hope for this to happen while there is still time, so that we can also have heroes worthy of Dostoevsky even in this age.

Having been gifted with the ability to dive deep into the realm of the subconscious, Dostoevsky soon realized how unpredictable human beings can be. His underground man insults his readers, then apologizes and berates himself, which culminates in his becoming aggressive, only to calm down a moment later. And the circle is repeated. He constantly pulls the rug under his own feet, and at the same time he is aware that he is trapped in the labyrinth of his character. He confesses and announces: “Hell, that’s me.”

Long before Sartre, and more disturbingly than Dante, Dostoevsky described hell in a similar manner, but more accurately: “I maintain that hell is the suffering of being unable to love.” Unlike Sartre, this definition of hell does not seek the cause of torture in others but only in oneself, “in my inability to relate to the ‘other,’ the tragic loneliness of my existential self-containedness, of my ‘freedom’,” as Yannaras lucidly observed.

By saying that “to love a person means to see him as God intended him to be,” Dostoevsky seems to have set eschatological expectations as the measure of existence in history. By not embellishing the conflicting image of the inhospitable world before him, Dostoevsky composes a grand symphony of life in which paraphony, cacophony and harmony alternate, and moreover coexist, giving us a complex but compelling anthropology.

When Dostoevsky rearranges the coordinates of reality in his storytelling (in one story, the snow falls horizontally), he helps the reader to flee from the comfort of the casual narrative. A grave monotony reigns over many devilish forgers of better and brighter futures (Verkhovensky, Stavrogin), whereas those who cherish life, even in bad times and with notable fluctuations in their fortunes, give off a resonance of hope. After all, the latter resonate with a universal frequency, which is why only such people experience a resolving crescendo that comes after a change of heart (metanoia) and repentance.

Although a profound psychologist, Dostoevsky does not assess the spiritual rebirth of man in Christ by human criteria alone, nor does he provide a documentary account of such a process. What he does is help us to see how much we have fallen into the trap of self-deception so that we do not dare begin the fight against inherent sinfulness. Whenever we achieve some moral victory, vainglory so muddles our minds that we begin to think that the pride engendered reflects our true self. Alyosha, though, tells his crafty brother: “The ladder’s the same. I’m at the bottom step, and you’re above, somewhere about the thirteenth. That’s how I see it. But it’s all the same. Absolutely the same in kind.”

Dostoevsky’s novels illustrate all poles of the antinomy of life, and they can stir us up in this age of transhuman technology. We hope for this to happen while there is still time, so that we can also have heroes worthy of Dostoevsky even in this age.

I am so very pleased to be here for this occasion celebrating the Exhibit: Saved by Beauty: Dostoevsky in Boston, and its special artist, our beloved friend, Bishop Maxim, the spiritual father of the Serbian Orthodox Church’s Diocese of Los Angeles and Western America.

As you know, His Grace is known for his aesthetic sensibilities and erudition, as well as for his outstanding command of the Greek language. His sophistication and artistic accomplishment are highlighted by his natural humility and piety. In this way, he is a most appropriate exegete of the complex character of Dostoevsky. For the great Russian novelist wove his narrative from every stratum of the Orthodox world he inhabited. Beauty, to be sure, but he was not afraid to look at the ugliness that can inhabit men’s souls, too.

And so, I am glad that this exhibition is here to remind us of the work ahead, and to remind us that to kalon kai to agathon—the beautiful and the good—are not merely two sides of the same coin, but in fact are the same thing. Thank you, and special thanks to you, my dear brother, Bishop Maxim.

Greek Archbishop Elpidophoros of America

Maliotis Cultural Center, Brookline, Massachusetts

June 24, 2022

As you know, His Grace is known for his aesthetic sensibilities and erudition, as well as for his outstanding command of the Greek language. His sophistication and artistic accomplishment are highlighted by his natural humility and piety. In this way, he is a most appropriate exegete of the complex character of Dostoevsky. For the great Russian novelist wove his narrative from every stratum of the Orthodox world he inhabited. Beauty, to be sure, but he was not afraid to look at the ugliness that can inhabit men’s souls, too.

And so, I am glad that this exhibition is here to remind us of the work ahead, and to remind us that to kalon kai to agathon—the beautiful and the good—are not merely two sides of the same coin, but in fact are the same thing. Thank you, and special thanks to you, my dear brother, Bishop Maxim.

Greek Archbishop Elpidophoros of America

Maliotis Cultural Center, Brookline, Massachusetts

June 24, 2022

I ask myself whether America is approaching its own 1917 moment equivalent to that of Russia in October/November of 1917, a moment of radical political and social iconoclasm, a moment when in the effort at reform of real problems, we lurch rather headlong, as Holy Russia once did, into an abyss with no visible bottom. If we in America in fact are at a 1917-level moment of peril, it is obviously because we as Americans have set out upon a course of reform from some of our past mistakes, and have not yet figured out how to combine the best of the new with the best of the old. Or, because at the moment of any reform, there is liable to rise to the surface a fair measure of suppressed rage that strikes out blindly for revenge. Or, because when certain suppressing controls are lifted, there invariably appear a fair number of scalawags and malcontents eager to take advantage of the general uncertainty and chaos to work their own malice.

Or, more generally, because when we seek to move to a higher realm of social order, we must face the fact that we don’t quite yet know what we’re doing. We don’t recognize the music; we haven’t learned the steps; we aren’t familiar with the social etiquette and protocol, so to speak, of the new social place to which we are headed. Of necessity, we stumble blindly until we’ve become acclimated.

But if we in the West are not sure where we’re headed—just that it’s uncharted territory, that it perhaps will involve the dethroning of what we take to be an array of idols propping up our political, economic, and gender orders—it’s helpful to ask where we’ve been, or how we reached a moment of such crisis in the first place. For me, the longstanding Western challenge—and the peril we face now as we seek to extricate ourselves from that crisis—comes down to the role of beauty, and to the absence of the third of Socrates’ three great Transcendentals in our academic, everyday, and official concerns. Our crisis began when we ceased to prioritize the beautiful, and simultaneously divorced Beauty from the realm of reason, placing it instead within the realm of opinion, prejudice, or bias. For Truth, we in the West have long held a great reverence—in the modern era, we called it Science, or sometimes Social science.

For Goodness, we have a near obsession—our word for the Good in the modern era, is “Technology,” and we obsess about the social technology known as “policy” and about possible new government or corporate frameworks for addressing our problems. That is to say, we have reduced “the Good” to the useful, and thereby reduced Goodness to Utility. Thus, our public discourse is frequently characterized by rudeness and boorishness from all sides, and our public protests veer easily into destruction of property and the targeting, by both sides, of bastions of state power.

For the eastern Church, the aesthetic sense is already a cognitive faculty. Think of the long history of life on this planet, and the near-constant occupation of every living thing with “making sense” of its environment in order to survive. If this raw physical sensing was irrational, then no organism would have survived. Rather, from single celled organisms to humpback whales, from slime molds to flocks of birds, every living thing is processing information about itself and its environment, and reacting in the appropriate way for its own survival. Clearly, sensing and reacting can be already a form of reason.

We call this process of rational recalibration “asceticism,” and for 2,000 years we have known asceticism to be the foundation of thinking clearly about the world. For us, purified encounter with serious art—with the grammar of artistic perfection in literature, in music, in architecture, here today in painting—and above all with the grammar of imperfect perfection found in liturgical art—is the foundation of a social order that is simultaneously just and merciful, that can handle gender as an icon without reducing it to an idol, that can humbly submit to sexual morality without becoming beguiled into extreme statements about those around us.

Dr. Timothy Patitsas

Or, more generally, because when we seek to move to a higher realm of social order, we must face the fact that we don’t quite yet know what we’re doing. We don’t recognize the music; we haven’t learned the steps; we aren’t familiar with the social etiquette and protocol, so to speak, of the new social place to which we are headed. Of necessity, we stumble blindly until we’ve become acclimated.

But if we in the West are not sure where we’re headed—just that it’s uncharted territory, that it perhaps will involve the dethroning of what we take to be an array of idols propping up our political, economic, and gender orders—it’s helpful to ask where we’ve been, or how we reached a moment of such crisis in the first place. For me, the longstanding Western challenge—and the peril we face now as we seek to extricate ourselves from that crisis—comes down to the role of beauty, and to the absence of the third of Socrates’ three great Transcendentals in our academic, everyday, and official concerns. Our crisis began when we ceased to prioritize the beautiful, and simultaneously divorced Beauty from the realm of reason, placing it instead within the realm of opinion, prejudice, or bias. For Truth, we in the West have long held a great reverence—in the modern era, we called it Science, or sometimes Social science.

For Goodness, we have a near obsession—our word for the Good in the modern era, is “Technology,” and we obsess about the social technology known as “policy” and about possible new government or corporate frameworks for addressing our problems. That is to say, we have reduced “the Good” to the useful, and thereby reduced Goodness to Utility. Thus, our public discourse is frequently characterized by rudeness and boorishness from all sides, and our public protests veer easily into destruction of property and the targeting, by both sides, of bastions of state power.

For the eastern Church, the aesthetic sense is already a cognitive faculty. Think of the long history of life on this planet, and the near-constant occupation of every living thing with “making sense” of its environment in order to survive. If this raw physical sensing was irrational, then no organism would have survived. Rather, from single celled organisms to humpback whales, from slime molds to flocks of birds, every living thing is processing information about itself and its environment, and reacting in the appropriate way for its own survival. Clearly, sensing and reacting can be already a form of reason.

We call this process of rational recalibration “asceticism,” and for 2,000 years we have known asceticism to be the foundation of thinking clearly about the world. For us, purified encounter with serious art—with the grammar of artistic perfection in literature, in music, in architecture, here today in painting—and above all with the grammar of imperfect perfection found in liturgical art—is the foundation of a social order that is simultaneously just and merciful, that can handle gender as an icon without reducing it to an idol, that can humbly submit to sexual morality without becoming beguiled into extreme statements about those around us.

Dr. Timothy Patitsas

In our time, when there is a tendency to rob everything of their original meaning and purpose, this exhibit appears as an oasis of the Logos and a festival of the Spirit. Through Fyodor (Russian pronunciation of Theodore) God (Theos) offers Himself to us as a gift (doron). It is hard to tell what a greater surprise is: through whom or to whom He offers Himself—in how fragile vessels He is willing to abide. Through a person and literary work of a suffering man who is seemingly, like his characters, falling apart, but hungry and thirsty for Christ, the Truth is concealed or revealed to everyone in accordance with their own, conscious, or unconscious, desire for Him. Every exhibited painting is a unique testimony to it.

Each of the authors, touched by the flame of inspiration, speaks of the same using a different tongue, to invite us to the unity and community of the Pentecost. It is as logical as the dream of a ridiculous man, as the Brothers Karamazov, the cubism in Orthodox iconography or Dostoyevsky in Athens. This logic transcends the fallen, calculated “logic”, which enslaves. Compared to that “logic”, this one is non-logical for it is the logic of the Logos, the logic of Love, which sets us free and hence it is compellingly and essentially needed, as therapeutic and salvific.

In New York, a place of cosmic outreach, the culture stemming from the experience of the cult, is offered to the suffering world without preaching, but rather compassionately. By its blessed mission even the disfigured and abused words such as “technical” and “technology” are redeemed and given back their pristine meaning and beauty.

Each of the authors, touched by the flame of inspiration, speaks of the same using a different tongue, to invite us to the unity and community of the Pentecost. It is as logical as the dream of a ridiculous man, as the Brothers Karamazov, the cubism in Orthodox iconography or Dostoyevsky in Athens. This logic transcends the fallen, calculated “logic”, which enslaves. Compared to that “logic”, this one is non-logical for it is the logic of the Logos, the logic of Love, which sets us free and hence it is compellingly and essentially needed, as therapeutic and salvific.

In New York, a place of cosmic outreach, the culture stemming from the experience of the cult, is offered to the suffering world without preaching, but rather compassionately. By its blessed mission even the disfigured and abused words such as “technical” and “technology” are redeemed and given back their pristine meaning and beauty.

The exhibition for Dostoevsky was an idea of Maxim Vasiljevic, Bishop of Los Angeles and Western America. The artists of the group immediately embraced this idea and worked each one in his own particular style and with different artistic media. Some artists tried to picture a portrait of the great writer and some others attempted to illustrate characters of his novels. All of them, as I believe, respected Dostoevsky’s spirit and the atmosphere of his narrations.

The exhibition is an homage to the great writer, and I would like to believe that is the first but not the last of events that the Orthodox Church in the USA will organize in order good quality arts to become again part of the daily life of people and simultaneously organic part of the ecclesiastic life.

The group “Ochre” was established in 2018 in Athens and its main goal is to continue the traditional Byzantine style painting in our postmodern world. Based on the belief that this style is a complete and integrated painting system the artists joined the group attempt to use this artistic language not only in rendering religious themes, but in visualizing the contemporary life, the feelings, and the anxieties of contemporary people and mostly to capture and render in visual terms their hopes and their vision for a better world. A world characterized by reconciliation, peace, love and above all by the unity of a community.

We as artists believe that this artistic language, the Byzantine painting system, has elaborated and has developed for centuries in order for the ethos and the spirit of the ecclesiastical life to be properly render in visual terms. For that reason, we believe that this language can serve the needs for expression of contemporary artists who are looking for a vehicle for expressing their spiritual inquiries.

Byzantine painting tradition, which was and is always open to a dialogue with other contemporary artistic trends, is a good and suitable language for presenting the daily life, the nature and the human adventure in a mode that elevates everything at a stage of sacredness.

George Kordis

The exhibition is an homage to the great writer, and I would like to believe that is the first but not the last of events that the Orthodox Church in the USA will organize in order good quality arts to become again part of the daily life of people and simultaneously organic part of the ecclesiastic life.

The group “Ochre” was established in 2018 in Athens and its main goal is to continue the traditional Byzantine style painting in our postmodern world. Based on the belief that this style is a complete and integrated painting system the artists joined the group attempt to use this artistic language not only in rendering religious themes, but in visualizing the contemporary life, the feelings, and the anxieties of contemporary people and mostly to capture and render in visual terms their hopes and their vision for a better world. A world characterized by reconciliation, peace, love and above all by the unity of a community.

We as artists believe that this artistic language, the Byzantine painting system, has elaborated and has developed for centuries in order for the ethos and the spirit of the ecclesiastical life to be properly render in visual terms. For that reason, we believe that this language can serve the needs for expression of contemporary artists who are looking for a vehicle for expressing their spiritual inquiries.

Byzantine painting tradition, which was and is always open to a dialogue with other contemporary artistic trends, is a good and suitable language for presenting the daily life, the nature and the human adventure in a mode that elevates everything at a stage of sacredness.

George Kordis

OCHRE is an informal group of painters, who have contributed to the traditional Orthodox iconography but at the same time are in dialogue with the modern artistic trends. The exhibition is organized with great passion by the 13 artists.

The exhibit is characterized by great pluralism. It hosts various currents and artistic trends, which are in a harmonious dialogue with each other. One sees Byzantine elements conversing with impressionist, expressionist, cubist, abstract, as well as features of street art, graffiti, etc.

The works emit a deep study and understanding of Dostoevsky’s novels. It is very important that the painters have so seriously studied the great writer and philosopher at a time when electronic images and soap operas distract readers from great and essential works and wider Literature.

It is obvious that we have before us an important robust and fruitful spiritual event, which will be a station for the artistic events in Greece and it is not excluded that its message will spread to other countries.

Artists: Fr. Stamatis Skliris, George Kordis, Bp. Maxim Vasiljevic, Babis Pylarinos, Costas Labdas, Maria Panou, Konstantinos Kougioumtzis, Despina Karantani, Giannoulis Liberopulos, Christos Kexagioglou, Nektarios Mamais, Nektarios Stamatelos, Fothis Barthis.

The exhibit is characterized by great pluralism. It hosts various currents and artistic trends, which are in a harmonious dialogue with each other. One sees Byzantine elements conversing with impressionist, expressionist, cubist, abstract, as well as features of street art, graffiti, etc.

The works emit a deep study and understanding of Dostoevsky’s novels. It is very important that the painters have so seriously studied the great writer and philosopher at a time when electronic images and soap operas distract readers from great and essential works and wider Literature.

It is obvious that we have before us an important robust and fruitful spiritual event, which will be a station for the artistic events in Greece and it is not excluded that its message will spread to other countries.

Artists: Fr. Stamatis Skliris, George Kordis, Bp. Maxim Vasiljevic, Babis Pylarinos, Costas Labdas, Maria Panou, Konstantinos Kougioumtzis, Despina Karantani, Giannoulis Liberopulos, Christos Kexagioglou, Nektarios Mamais, Nektarios Stamatelos, Fothis Barthis.

Artworks

- "Dostoevsky", acrylic on canvas, 2012, Stamatis Skliris

- "The Underground Man", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Stamatis Skliris

- "Sonia Marmeladova", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Stamatis Skliris

- "Dostoevsky", Digital Painting, Giclee print, 2021, George Kordis

- "Annia Snitkina", Digital Painting, Giclee print, 2021. George Kordis

- "White Nights by Dostoevsky", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Stamatis Skliris

- "Dostoevsky", acrylic on canvas, 2018, Stamatis Skliris

- "Smerdyakov", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Stamatis Skliris

- "Dostoevsky in the Prison Ship", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Stamatis Skliris

- "Fyodor Dostoevsky", acrylic on cardboard, 2021 Bishop Maxim

- "The Christ of Dostoevsky", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Karamazov", acrylic on cardboard, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Alexei Ivanovich and Polina Alexandrovna", 2021, acrylic on canvas, Bishop Maxim

- "Klara Olufsievna", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Return to a Dream", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Despina Karantani

- "Starets Zosima", acrylic on cotton fabric, 2021, Konstantinos Kougioumtzis

- "Stavrogin", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "A Repetition", digital, 2021, Maria Panou

- "Elder Tikhon", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Monologue from Underground", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Sonya Marmeladova la Fayum", acrylic on woodboard, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Stairs to the Underground", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Brothers Karamazov", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Myshkin", acrylic and gold leaves on canvas, 2020, Costas Labdas

- "Underground", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Giannoulis Liberopulos

- "I'm a Ridiculous Man", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Christos Kexagioglou

- "Fyodor Dostoevsky Rapt in His Thoughts", digital, 2021, Babis Pilarinos

- "The Dream of a Ridiculous Man", digital, 2021, Maria Panou

- "How Ends a Poem", wood engraving, 2021, Fothis Barthis

- "You will never reach your destination if you stop and throw stones at every dog that barks", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Nektarios Stamatelos

- "Nastasya Filippovna 2", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Ivan Karamazov", digital painting, 2020, Bishop Maxim

- "The Grand Inquisitor", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Fyodor Dostoevsky and Maria Skobtsova", acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Dostoevsky in His Wet Loneliness", acrylic and ink on canvas, 2021, Nektarios Mamais

- "A Story of Sonya Marmeladova's Love", acrylic on canvas, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "Christ and the Grand Inquisitor", acrylic on cardboard, 1990, Stamatis Skliris

- "Netochka Nezvanova 2", acrylic on canvas, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "Crystal Palace: a utopian place of purely rational living", acrylic on canvas, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "The Last Look of Nastasya Filippovna" (female hero of The Idiot), acrylic on canvas, 2021, Bishop Maxim

- "Amour Proper of Nastasya Filippovna", acrylic on canvas, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "Christ and the Grand Inquisitor", acrylic on canvas, by Bishop Maxim, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "Abbas Issak of Syria and Dostoevsky", acrylic on canvas, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "Unknown Dostoevsky's Character", acrylic on canvas, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "The Wedding That Didn't Happen—Myshkin and Nastasya", acrylic on canvas, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "Starets Joseph of Optina", acrylic on canvas, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "Dostoevsky's Room", acrylic on canvas, 2022, Bishop Maxim

- "Krotka: A Gentle Creature by Dostoevsky" (Fayum style), acrylic on canvas, 2023, Bishop Maxim

- "Alyosha Karamazov", acrylic on canvas, 2023, Bishop Maxim

Meet The OCHRE Group

Ochre is a group of contemporary painters whose members share a love of the art of iconography and its centuries-long history, regardless of whether that love is expressed though what is called the art of Byzantine painting, or through other styles of painting.

The primary aim of the participants in this group is to enter into a creative dialogue with the visual and theological body of the art of iconography, with the ultimate goal of creating contemporary icons able to function within the sphere of Christian worship and to meet the needs of the faithful.

At the same time, since the members of this group believe that ecclesiastical art, like every aspect of the life of the Church, can be expressed in a multitude of ways, which, however, are connected by a shared logos, the members of Ochre maintain that the tradition of the art of iconography also affords a range of possibilities for the creation of paintings that are not necessarily restricted to ecclesiastical themes.

Maxim Vasiljevic

Stamatis Skliris

George Kordis

Babis Pilarinos

Maria Panou

Kostas Lavdas

Nektarios Mamais

Christina Papatheou Douligeri

Giannoulis Liberopoulos

Fotis Varthis

Dimitra Psychogiou